“Bruce A. Wooley, a former Chairman of the Electrical Engineering Department of Stanford University, has said that without a doubt the finest university in the world – in the world – preparing electrical engineering undergraduates is Sharif University in Tehran. 15 of them were accepted in the graduate programme at Stanford [last year], given straight green cards and brought into the country. There is an innate intelligence to this country.”

– Terrence Ward, Author of Searching for Hassan

The ‘secret’ only dawned on the leaders at Stanford University as they once realised that a large number of foreign students were beginning to do really well on some very hard PhD qualifying exams. Examining a bit further, they noticed that the disproportionate number of these students came not from one country in Asia but from a single university – The Sharif University of Technology in Tehran.

For Sharif University, this has been a culmination of several decades of hard work and the realisation of a dream from 50 years ago.

Creme de la creme

Sharif attracts, literally, the cream of Iranian society each year. Every year, 1.5 million young Iranians take a national university entrance exam, or “concours.” Of the 500,000 who pass and are entitled to free higher education, only the top 800 can attend Sharif – that is just over 5 students out of every 10,000. (1) This is a remarkable level of selectivity. Compare that with MIT, for instance, where the acceptance rate at the undergraduate level is about 8-10% of those who apply and one could begin to get a sense of whats happening here.

Sharif attracts, literally, the cream of Iranian society each year. Every year, 1.5 million young Iranians take a national university entrance exam, or “concours.” Of the 500,000 who pass and are entitled to free higher education, only the top 800 can attend Sharif – that is just over 5 students out of every 10,000. (1) This is a remarkable level of selectivity. Compare that with MIT, for instance, where the acceptance rate at the undergraduate level is about 8-10% of those who apply and one could begin to get a sense of whats happening here.

“The selection process [gives] universities like Sharif the smartest, most motivated and hardworking students” in the country, says Mohammad Mansouri, a Sharif alum (’97) who is now a professor in New York. (1)

Take into the account the fact that Iran’s education system at the school and college level is already quite competitive and, unlike many other countries, most Iranian parents prefer to send their sons and daughters to study sciences and engineering rather than law or business, for instance, adds all the more rigor to this already airtight process.

One testament of the Iranian schools system’s emphasis on STEM is the fact that Iran has become a major player in the international Science Olympiads taking home trophies in physics, mathematics, chemistry and robotics. As a testament to this newfound success, the Iranian city of Isfahan recently hosted the International Physics and Mathematics Olympiads —an honor no other Middle Eastern country has enjoyed.

No wonder then that Sharif University has produced some remarkably brilliant and prolific alums. Maryam Mirzakhani, the first woman ever to have won the Fields Medal of Mathematics – often referred to as the Nobel Prize of Mathematics, but just an order of magnitude more prestigious – is an alum of Sharif University. Others include Behzad Razavi, Professor of Electronics at UCLA, Mohammad Shahidehpour, the Associate VP of Research at Illinois Institute of Technology, and Mehdi Setareh, the professor of architecture at Virginia Tech. (2)

In addition to those who have excelled in science and technology, Sharif also has been an alma mater to several political, social, and cultural figures such as Ali Akbar Salehi (a former President of the University and a Vice President of Iran), Morteza Alviri, former Mayor of Tehran, Ali Larijani, speaker of Majlis and former presidential candidate, Elshan Moradi (Chess Grandmaster), and Peyman Yazdanian (Music Composer). (2)

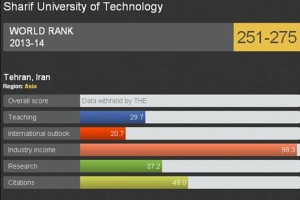

Today Sharif University has a student population of more than 9000 – of which 700 are pursuing doctrates – and 500 faculty members in 15 disciplines. It carries out a vast majority of the Industry-funded R&D in the country and is consistently ranked as No. 1 University nationally and among 500 top universities (between 250-350) around the world over the last 5 years.

Today Sharif University has a student population of more than 9000 – of which 700 are pursuing doctrates – and 500 faculty members in 15 disciplines. It carries out a vast majority of the Industry-funded R&D in the country and is consistently ranked as No. 1 University nationally and among 500 top universities (between 250-350) around the world over the last 5 years.

Times Higher Education also ranked Sharif University 1st in the Middle East, 6th in Asia, and 27th in the world in top 100 universities under 50. (6)

However, Sharif was always not this utopia of scientific and technological prowess. It has had its fair share of ups and downs as well.

Ambitious Beginnings

Established in 1966 by Reza Shah Pahlavi – the West-aligned Shah of Iran – as The Aryamehr University of Technology (AMUT) with an idea and effort to steer the Iranian Higher Education Model towards the US tradition. Formed alongside several other schools established in collaboration with Harvard, Georgetown, and Columbia, AMUT was to become the technological powerhouse to drive Iran’s science and industry much like its inspiration, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) had done for America. Much like MIT, it was to provide technical education where interdisciplinary research centers transcended traditional disciplinary departments. (3)

The Shah explained that he wanted an Iranian MIT, not an Iranian Harvard or Princeton, because Iran needed “a problem-solving type of education. (3) The final master plan of the University produced by Arthur D. Little and a number of consultants from the US clearly laid out the vision:

“The main idea in this organization of instruction is to organize the academic activities on the major technological problems of the country instead of the usual disciplines. The reality of the needs of Iranian society and the aspirations for Iran’s accelerated development requires that their educational system should not be a copy of the obsolete aspects of western systems by a lag of twenty years; instead, it must be based on Iranian culture and societal characteristics.”

And, herein lay the important twist.

At the Crossroads of Science and Religion

The Shah appointed Seyyed Hossein Nasr (the first Iranian to graduate from MIT) as AMUT’s chancellor in 1972 with the mandate to create an institution that created and built its own cultural identity within the Persian tradition. Nasr was the ideal man for the job. Having done his undergraduate from MIT in the sciences, he later moved to philosophy and history of science finishing his PhD from Harvard. (5)

The Shah appointed Seyyed Hossein Nasr (the first Iranian to graduate from MIT) as AMUT’s chancellor in 1972 with the mandate to create an institution that created and built its own cultural identity within the Persian tradition. Nasr was the ideal man for the job. Having done his undergraduate from MIT in the sciences, he later moved to philosophy and history of science finishing his PhD from Harvard. (5)

As a condition of his acceptance, Nasr asked for the opportunity to develop a vigorous program in Islamic history, philosophy, and culture to complement the engineering training. “What I wanted to do as president of the university,” Nasr explained, “was to create an indigenous technology in Iran, and not simply keep copying from Western technology.” (3)

Nasr’s pioneering effort led Aryamehr to create one of the first graduate programs in the Islamic world in the philosophy of science based upon the Islamic philosophy of science. (5)

In addition, ambitious plans for a collaboration between MIT and AMUT were laid out. Nasr wrote to MIT President Jerome Wiesner (his batch mate from MIT days) and sought formal help and collaboration. (3) Plans were made of creating opportunities for AMUT faculty to take sabbaticals at MIT, for AMUT graduate students to complete their graduate training at MIT, and joint research programs between the two schools.

In a pattern that was to be repeated by US Universities many times over in the Persian Gulf later, MIT agreed to set up research centers at MIT that were ‘supported’ by Iran and supposed to engage in joint R&D with AMUT professors. Energy was high on the agenda in the 197os and Iran agreed to pay towards a $50 million Energy Research Center at MIT. (3) Flushed with oil wealth, Shah went on a buying spree. Plans were also discussed to entertain training in nuclear engineering for certain members (30 each year) of the Iranian Atomic Energy Commission.

Events would soon overtake these ambitious plans.

Politics trumps science trumps politics again

Nasr resigned in 1975 shortly before the overthrow of the Shah’s regime. Having opened their minds of philosophy, history, religion, and culture, AMUT’s students had become deeply engaged in the conversations that preceded and followed the Islamic Revolution in Iran.

Nasr resigned in 1975 shortly before the overthrow of the Shah’s regime. Having opened their minds of philosophy, history, religion, and culture, AMUT’s students had become deeply engaged in the conversations that preceded and followed the Islamic Revolution in Iran.

Nasr later reminisced on the dilemma he faced:

“Technology is not value free. It brings with it a kind of culture of its own. And so once you get into it on a high level you can become very easily alienated from your own culture and that creates a breeding ground for the worst kind of political activity. And that was also one of the reasons why the Shah paid so much attention to the new university. He said we must do everything possible to have our own scientists and engineering, to create our own technology, without this social and political explosion.”

After the revolution, a vast majority of the professors left AMUT – many went to the United States. The government of the Islamic Republic renamed the AMUT Sharif University after a Martyr of the revolution. It also separated the campus in Isfahan to create the Isfahan University of Technology. Gradually some of those who had left or were studying abroad at the time of the revolution returned – motivated to serve the revolution. (3)

While politics remained, though in a somewhat mellowed form, Sharif University has gradually become the kind of scientific and technological powerhouse that was the Shah’s vision. But it also became a lot more. As home to Iran’s best and brightest it also became a powerhouse of political ideas and the revolutionary ideology. Today, being a Sharif student is not only ones ticket abroad to the best Universities of Stanford, MIT, and Oxford but also to the corridors of power in Tehran as a substantial number of the student political leaders trained at Sharif gradually make their way to the very top of the echelons of power in Iran.

Iran’s dream of creating an MIT has been redeemed in both intended and unintended ways.

References: